The most precise timekeepers ever made, atomic clocks, might one day help robotic and crewed missions on Mars stay in sync with each other, as well as enable the equivalent of GPS on the red planet. But, as Einstein made clear, time flows at different rates depending on where you are. Now scientists have estimated the speed at which clocks tick on Mars—an average of 477 millionths of a second faster than clocks on Earth per day. These findings might suggest ways in which future networks on Mars can avoid problems such clock differences might produce.

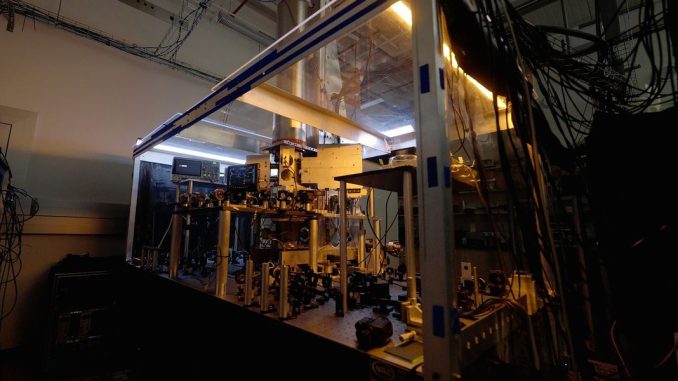

Atomic clocks monitor the vibrations of atoms. Optical atomic clocks, which use intersecting laser beams to entrap and monitor the atoms, are currently accurate down to 1 attosecond, or a billionth of a billionth of a second. These clocks have many applications besides keeping time—for example, they are key to the precisely timed signals that GPS and other global navigation satellite systems rely on to help users pinpoint their own locations.

However, because the gravity of massive objects warps spacetime, the rate of time passes different at different gravitational field strengths. In other words, the weaker a planet’s gravitational pull, the faster clocks on its surface tick. And the average strength of Mars’s gravitational pull is roughly three times as weak as Earth’s.

Mars Timekeeping and GPS Technology

In 2024, scientists at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) in Boulder, Colo. estimated the rate at which clocks ticked on the moon, which has an average gravitational pull about six times as weak as Earth’s. Given NASA’s plans for missions to Mars, the researchers have now analyzed timekeeping on Mars and detailed their research in a study published online on 1 December in The Astronomical Journal.

“With an understanding of these relativistic effects comes the hope that humans will someday become an interplanetary species,” says Neil Ashby, a professor emeritus of physics at the University of Colorado, Boulder, and an affiliate of NIST.

Using years of data collected from previous Mars missions, the scientists calculated the strength of gravity on the Martian surface. They also had to account for the how the gravitational effects of the sun and the other planets on Mars changed over time over the course of the Red Planet’s eccentric, elongated orbit.

Although clocks on Mars will on average tick 477 microseconds faster than on Earth per day, this value can increase or decrease by as much as 226 microseconds per day over the course of the Martian year, depending on effects from its celestial neighbors. Such variations could prove challenging when it comes to coordinating missions on Mars.

“Microseconds matter in navigation and communications,” says Bijunath Patla, a theoretical physicist at NIST. “Current 5G networks rely on microsecond-level synchronization. GPS clocks are synchronized to a few nanoseconds.”

This difference between Mars and Earth in clock speeds has not been a problem in past missions, because they relied “on one-way radio communication from ground stations on Earth and Mars,” Ashby says. “There was no need for rovers to be synchronized with each other.”

This new research “is important if you have multiple assets on Mars and they need to be in sync with each other and independent from Earth,” Patla says. “This could be important in returning to the same location for further exploration or prospecting.”

One possible way for Martian missions to deal with this difference between Earth and Martian clocks may be to deploy a GPS-like constellation of satellites around the planet so that both rover clocks and constellation clocks “share a common, Mars-centric system time,” Ashby says.

In such a scheme, only small local corrections would be needed to be applied when comparing clocks on Mars. “‘Mars system time’ would remain internally self-consistent and largely independent of Earth, and only the Earth-Mars link would require periodic calibration to account for the larger interplanetary offsets,” Patla says.

From Your Site Articles

Related Articles Around the Web

Be the first to comment